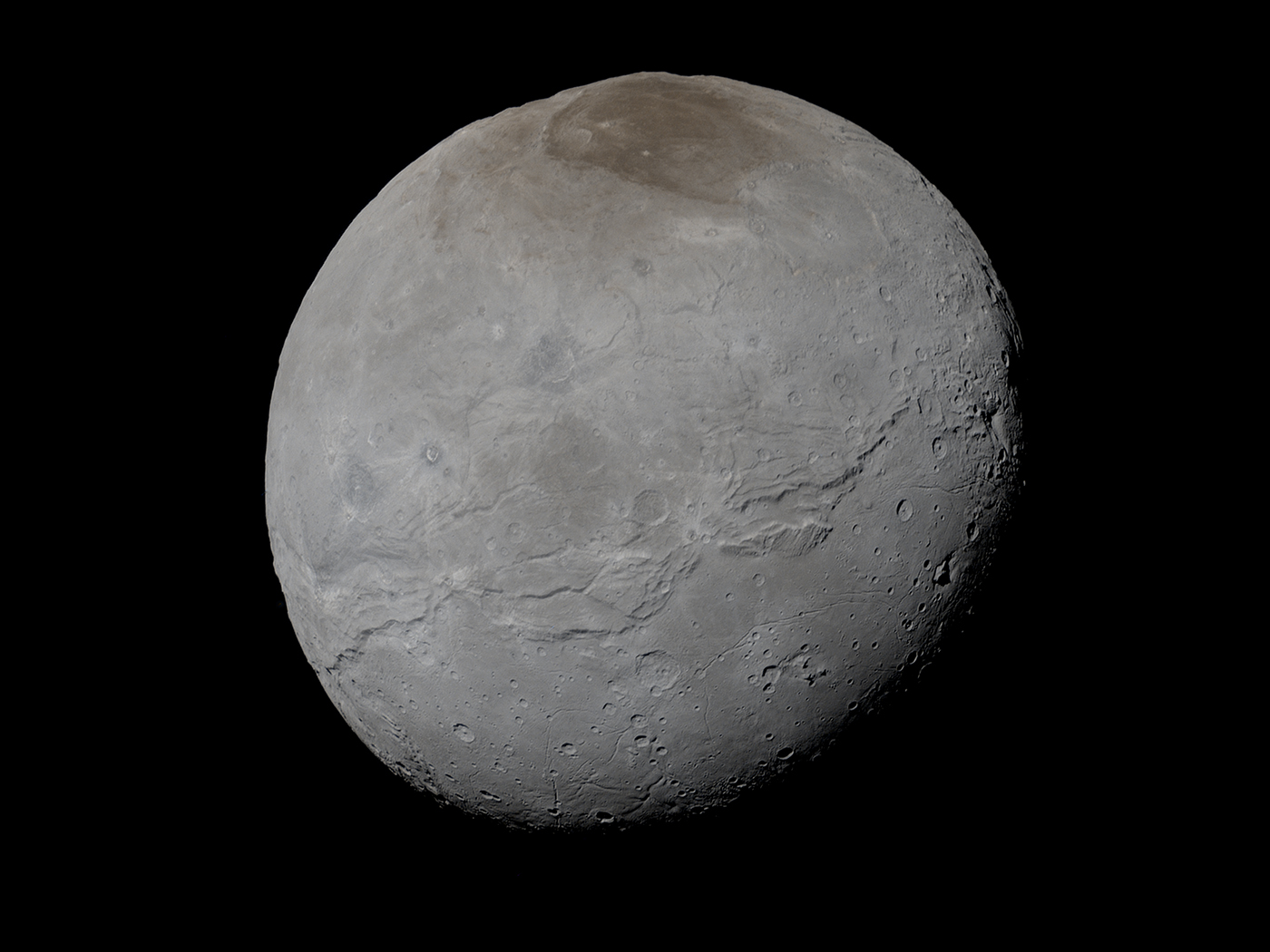

When the New Horizons space probe captured images of Pluto and its large moon Charon as it flew by in 2015, conventional scientists were surprised by the small number of craters in Charon’s southern hemisphere.1 This suggested a relatively young surface, despite Charon’s presumed age of over four billion years. How could they account for this?

Theorists proposed that a subsurface ocean developed on Charon billions of years ago. The large plain Vulcan Planitia was then repaved by cryovolcanism, “ice volcano” activity that erupts with gases and materials like water and ammonia rather than with lava.2 They suggested that the heat released by the freezing of that ocean could have powered this geological resurfacing. So, although tiny and distant Charon is presumably cold and dead today, theorists think it might have been warmer in the distant past.3

But there are problems with this idea. Writers of a 2023 paper pointed out difficulties with the idea that cryovolcanism on Charon could be the result of a freezing subsurface ocean billions of years ago. The researchers stated, “We find that current models of Charon's interior evolution predict ice shells that are far too thick to be fully cracked by the stresses associated with ocean freezing.”4 And after four billion years, one would think that a significant number of craters would have still have accumulated in Vulcan Planitia, even if it had been resurfaced eons ago.

Despite these difficulties, authors of a recent study used computer simulations to try to determine when such a freezing event would have occurred.2,5 They varied factors like starting temperature, porosity of Charon’s interior, and the amount of ammonia that might have been present in such a subsurface ocean. The authors stated,

Crucially, in no simulation across any parameter studied so far did the ocean fully freeze in a timeframe consistent with massive cryovolcanic eruptions before 4 Gyr [four billion years] ago. These results strongly suggest that if ocean freezing is the cause of the resurfacing of Vulcan Planitia at 4 Gyr ago, the details of the impact [that is supposed to have formed Pluto and Charon] matter.2

For this reason, theorists are planning future simulations in which Charon formed from an impact with Pluto, hoping that this will make their job easier. As noted by a popular science writer, “If a subsurface ocean on Charon is confirmed, even a frozen one, this could challenge our understanding of how planetary bodies form and evolve, especially so far from the sun.”5

Yes, it would—especially if such an ocean is still liquid water, because maintaining such a liquid would require a precise balance over billions of years:

Maintaining subsurface oceans against freezing over geological times requires a fine balance between internal heating and heat loss, and yet we have several pieces of evidence that Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, and other moons should be ocean worlds.6

How could such a “fine balance” be maintained for so long? If a frozen or partially frozen subsurface ocean is the cause of Charon’s apparent past cryovolcanism, such cryovolcanism would probably be easier to explain if one dropped the assumption of billions of years. And should Charon or other solar system bodies have liquid water today, this is far, far easier to explain if our solar system is just thousands of years old. The most straightforward explanation is that Pluto, Charon, and other objects in our solar system came into existence recently, just as Genesis attests.

References

- Charon’s Surprising, Youthful and Varied Terrain. NASA. Posted on nasa.gov July 15, 2015, accessed June 27, 2025.

- Noviello, J. L. et al. Modeling Charon’s Geochemical Evolution: Implications for Cyrovolcanism. 56th Lunar and Planetary Conference. Posted on hou.usra.edu, accessed June 27, 2025.

- Moore, J. M. et al. 2016. The geology of Pluto and Charon through the eyes of New Horizons. Science. 351 (6279): 1284–1293.

- Rhoden, A. R. et al. 2023. The Challenge of Driving Charon’s Cryovolcanism from a Freezing Ocean. Icarus. 392: 115391.

- Tognetti, L. Cryovolcanism and Resurfacing on Pluto’s Largest Moon, Charon. Universe Today. Posted on universetoday.com June 27, 2025, accessed June 27, 2025.

- Mace, M. Jupiter’s Moons Could Be Warming Each Other. University of Arizona. Posted September 10, 2020 at news.arizona.edu, accessed June 27, 2025.

* Dr. Jake Hebert is a research associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in physics from the University of Texas at Dallas.