ICR’s Column Project team recently finished work on the European continent, including Turkey and the area surrounding the Caspian Sea. We have now compiled stratigraphic data across four entire continents: North and South America, Africa—including the Middle East—and Europe.

ICR’s Column Project team recently finished work on the European continent, including Turkey and the area surrounding the Caspian Sea. We have now compiled stratigraphic data across four entire continents: North and South America, Africa—including the Middle East—and Europe.

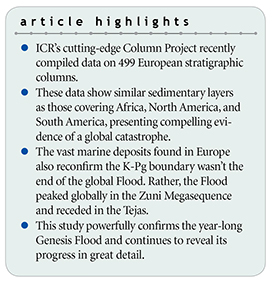

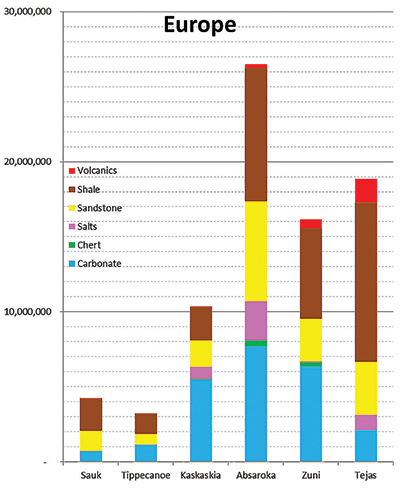

For Europe alone, we compiled 499 stratigraphic columns using oil industry wells, outcrops, and seismic data and published cross-sections across the continent. At each location, we input detailed lithology data and the megasequence boundaries (Figure 1).1 We used Rockworks version 17, a commercial software program for geological data.

The stratigraphic patterns across the first three continents were also found across Europe with slight differences. The Flood across Europe began in a limited extent in the Sauk, peaked in the Absaroka, and finally receded in the Tejas, the final megasequence. This is strong evidence for a global flood. All four continents we have studied share the same general pattern and timing of limited early flooding, followed by peak flooding, and then receding.

Europe Peaks in the Absaroka Megasequence

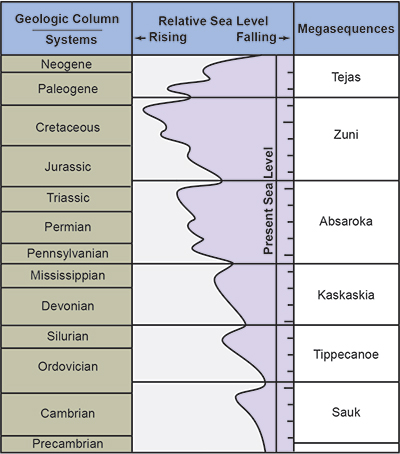

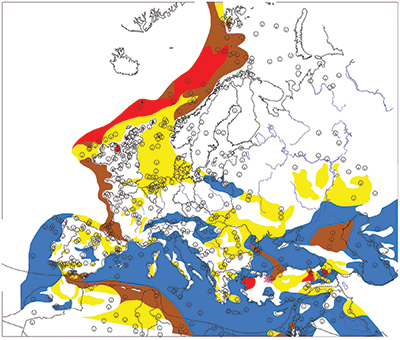

The earliest two megasequences (Sauk and Tippecanoe) show very limited coverage across Europe (Figure 2). This is the same pattern we observed across the other three continents. The totals across the four continents show the least volume and extent of sedimentary rocks in the earliest two megasequences. The later four megasequences (Kaskaskia, Absaroka, Zuni, and Tejas, respectively) show much more volume and surface extent.

The earliest two megasequences (Sauk and Tippecanoe) show very limited coverage across Europe (Figure 2). This is the same pattern we observed across the other three continents. The totals across the four continents show the least volume and extent of sedimentary rocks in the earliest two megasequences. The later four megasequences (Kaskaskia, Absaroka, Zuni, and Tejas, respectively) show much more volume and surface extent.

Oddly, Europe has a peak volume and surface coverage extent in the Absaroka Megasequence, which encompasses the Pennsylvanian through Lower Jurassic rocks. Most of the other continents peak a bit later. But the four continent totals still show the maximum extent and volume occurring in the fifth megasequence, the Zuni—Middle Jurassic through Cretaceous rocks (Figure 3).

We still believe this peak in the Zuni represents the high point of the Flood. In terms of stratigraphy, this falls near the end of the Cretaceous when most of the other continents also peak. This global high-water level is interpreted as Day 150 in the Flood year.

Europe Dominated by Lowlands and Shallow Seas

Why does Europe peak one megasequence earlier than most of the others? The answer seems to be in the pre-Flood configuration of Europe. Most of the pre-Flood European continent appears to have been lowlands and shallow seas, similar to the Dinosaur Peninsula concept for North America.2 The floodwaters were able to inundate most of Europe earlier than the other continents, giving a peak in sedimentary volume one megasequence earlier (Figure 4). In contrast, Africa, South America, and North America had more extensive pre-Flood uplands. Europe apparently only had uplands across the Scandinavian Peninsula and parts of Ukraine.

Rock Data Indicate Late Cenozoic Post-Flood Boundary

There is still debate among creation scientists about the location of the post-Flood boundary in the stratigraphic record. Some have claimed the K-Pg (formerly K-T) boundary marks the end of the Flood as well as the end of marine deposition across the continents. These scientists have insisted that the massive volumes of post-K-Pg sediments observed globally are merely the result of local, post-Flood catastrophes. In contrast, other creation scientists have argued that the K-Pg wasn’t the end of the Flood but that it continued through much of the Cenozoic rock record. ICR scientists agree with the latter position and interpret much of the Cenozoic strata as the receding phase of the Flood.

As we predicted, the results of the European study dramatically conflict with the K-Pg post-Flood boundary interpretation. The sedimentary rocks across much of central Europe indicate that marine depositional processes continued without interruption from the Cretaceous through the Upper Cenozoic (Figure 5). Many locations show continuous deposition of carbonate rocks across the K-Pg boundary from the Cretaceous through Miocene.

These results demonstrate that the Cenozoic rock deposit across Europe wasn’t due to highly speculative and improbable localized post-Flood catastrophes but rather to the receding phase of the global Flood itself. Massive marine deposits across such vast areas of the world indicate Flood processes were still active well into the Upper Cenozoic, possibly as high as the top of the Pliocene, where a major paleontological extinction event is observed,3 coinciding with the end of the Flood.

The other continents also support this Late-Pliocene Flood boundary interpretation, especially North America. The Cenozoic (Pliocene) Ogallala Formation covers about 174,000 square miles from Texas to South Dakota.4 While it’s only 20 to 40 feet thick in some locations, it increases to over 700 feet across much of the Great Plains. Igneous and metamorphic cobbles in the basal conglomerate of the Ogallala layer are sourced from the Rocky Mountains, hundreds of miles to the west.

Localized post-Flood catastrophism can’t explain the massive extent of the Ogallala Formation, just like isolated regional processes can’t explain the huge deposit of the Whopper Sand in the deep Gulf of Mexico.5 This sandstone is well over 1,000 feet thick and is found over 200 miles offshore. The only conceivable explanation for this vast deposit at the base of the Tejas Megasequence is its formation by the high- energy runoff conditions at the onset of the receding phase of the Flood as the continents and their mountain ranges were uplifting.

A Real Global Flood

The stratigraphy across Europe and the other three continents confirms a global flood occurred. All four continents in our study show a limited beginning to the Flood in terms of volume and extent, followed by a steady increase to a maximum water level, concluding with a receding phase that continued well into the Upper Cenozoic. Marine conditions across Europe prevailed well into the Miocene and Pliocene, dispelling the myth of a K-Pg end to the Flood. Stratigraphic data across four continents confirm the high Flood boundary and the truth of the Genesis Flood.

References

- Clarey, T. 2015. Grappling with Megasequences. Acts & Facts. 44 (4): 18.

- Clarey, T. 2015. Dinosaur Fossils in Late-Flood Rocks. Acts & Facts. 44 (2): 16.

- Pimiento, C. et al. 2017. The Pliocene marine megafauna extinction and its impact on functional diversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1: 1100-1106.

- Clarey, T. 2018. Palo Duro Canyon Rocks Showcase Genesis Flood. Acts & Facts. 47 (7): 10.

- Clarey, T. 2015. The Whopper Sand. Acts & Facts. 44 (3): 14.

* Dr. Clarey is Research Associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University.