Paleontologists have ranked Dinosaur Ridge as the top dinosaur track site in North America.1 Run by the nonprofit group Friends of Dinosaur Ridge, it was designated by the National Park Service as a National Natural Landmark.2 Located just 20 minutes west of Denver and just north of the town of Morrison, Colorado, it consists of a 1.1-mile-long rock outcrop that showcases strata from the lower Dakota Group and its underlying Morrison Formation. Over 300 individual fossil prints of dinosaurs and crocodiles are visible in the Dakota alone, with many darkened for easy visibility.

Paleontologists have ranked Dinosaur Ridge as the top dinosaur track site in North America.1 Run by the nonprofit group Friends of Dinosaur Ridge, it was designated by the National Park Service as a National Natural Landmark.2 Located just 20 minutes west of Denver and just north of the town of Morrison, Colorado, it consists of a 1.1-mile-long rock outcrop that showcases strata from the lower Dakota Group and its underlying Morrison Formation. Over 300 individual fossil prints of dinosaurs and crocodiles are visible in the Dakota alone, with many darkened for easy visibility.

Approximately 250,000 visitors take the self-guided walking tour, ride bikes, or take a bus tour each year.2 But visitors are only exposed to the conventional, old-earth explanation for this site. Few likely realize that this topographic ridge is a stunning reminder of the judgement of the global Flood.

Geology of Dinosaur Ridge

Dinosaur Ridge exposes sedimentary units from what uniformitarian geologists call the Cretaceous and Jurassic Systems. Both rock systems are part of the dinosaur fossil-bearing strata found across the globe. ICR geologists place them in the upper part of the Zuni Megasequence. This set of rock layers reflects the time during the Flood year when the water was approaching its highest level.3

The lower strata (Jurassic) are part of the famous Morrison Formation. This unit was named for the nearby town of Morrison, CO. In 1877, Arthur Lakes and Henry Beckwith found the very first dinosaur bones within the Morrison exposures on the west side of the ridge.4 These bones represented Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Diplodocus specimens.4

Conventional scientists think a series of rivers deposited the Morrison over many thousands of years or more. They believe the overlying Cretaceous layer, in some places called the Dakota Sandstone, was deposited over a vast amount of time by a shifting shoreline or beach environment with some influence from rivers along the coast.4 But do beaches and rivers preserve footprints and create fossil bones today? Not at all.

Footprints in Stone

Most of the dinosaur footprints along Dinosaur Ridge were made by Iguanodon-type dinosaurs. These animals walked on all fours, making footprints from eight to 18 inches long.5 But there are also many other prints found along the trail, including those belonging to crocodiles. Even bird tracks are preserved just north of the site.5

Most of the dinosaur footprints along Dinosaur Ridge were made by Iguanodon-type dinosaurs. These animals walked on all fours, making footprints from eight to 18 inches long.5 But there are also many other prints found along the trail, including those belonging to crocodiles. Even bird tracks are preserved just north of the site.5

In addition, the dinosaur footprints at Dinosaur Ridge are part of a massive line of tracks called the Dinosaur Freeway.5 These tracks extend south from Dinosaur Ridge hundreds of miles along the Colorado Front Range to parts of the high plains of Oklahoma and New Mexico.5 What could have caused these tracks to be preserved over such a vast region?

A Better Explanation: The Global Flood

Four observations testify that the global Flood best explains both the rocks and the fossils at Dinosaur Ridge.

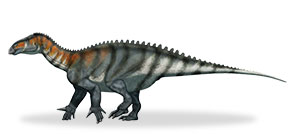

1. Evidence of water deposition

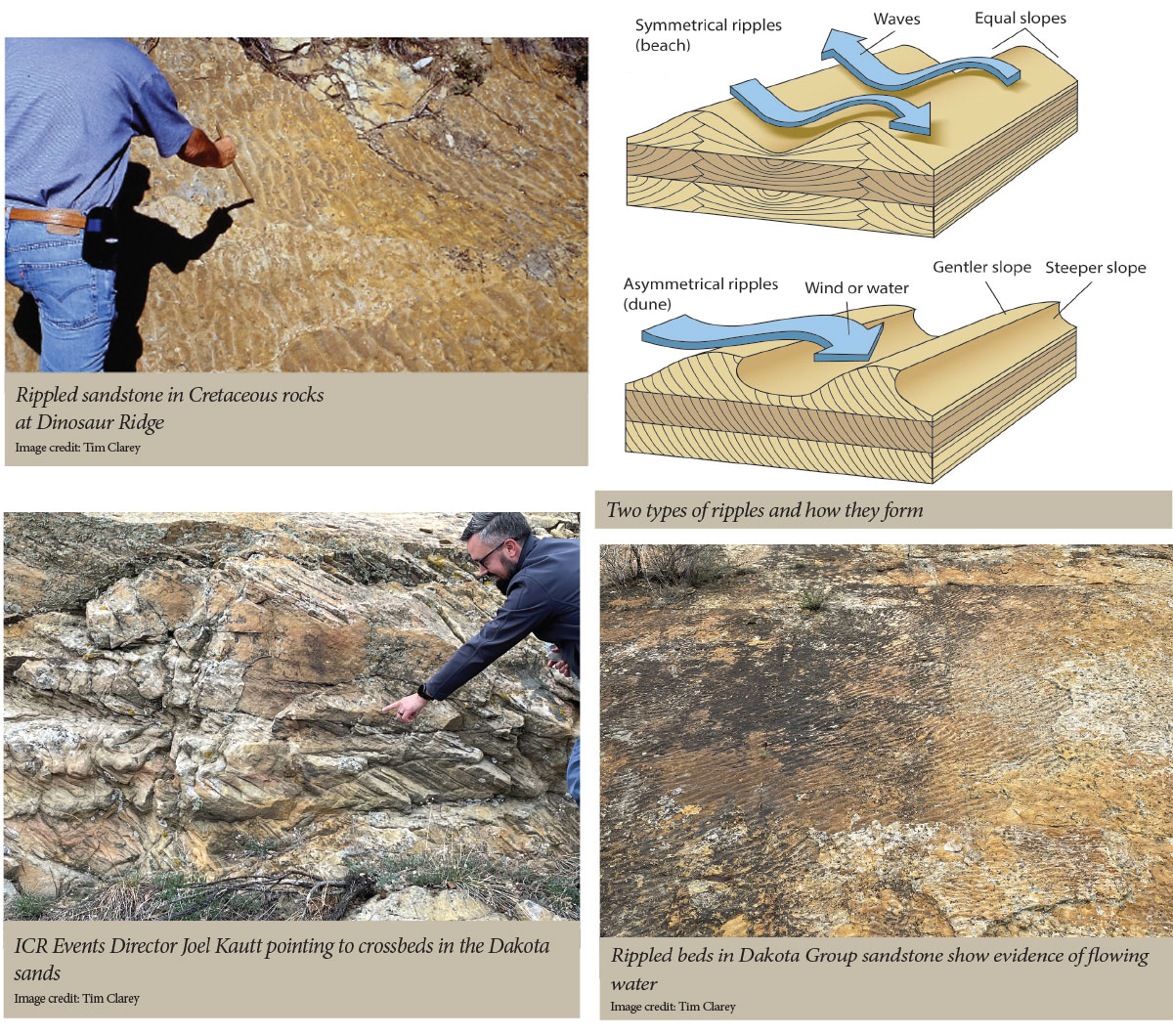

In outcrops and in well cores, the Dakota is full of ripples and cross-bedded sands.4,6 These sedimentary structures indicate water flow. Cross-bedded sands form as ripples or dunes migrate during energetic water flow. Moving water shoves sand grains up the back of the ripple. The sand then falls down the lee side where the grains stop, forming a bedform that appears to cut across the bedding.

Fossils found in the Dakota also reveal water’s influence. Many burrows and trails of worms and other invertebrates like crustaceans are found in the sandy sediment.4 And many of the crocodile tracks indicate they were swimming in shallow water, having left only scratches in the substrate.5

2. Rapid deposition of layers

Not only does the science point to a watery deposition, but several observations demonstrate that the Dakota Group was deposited right after the Morrison. First, in order to preserve tracks, prints, and ripples, they must be buried fast so they are not destroyed. Footprints on beaches or in rivers do not last long today.

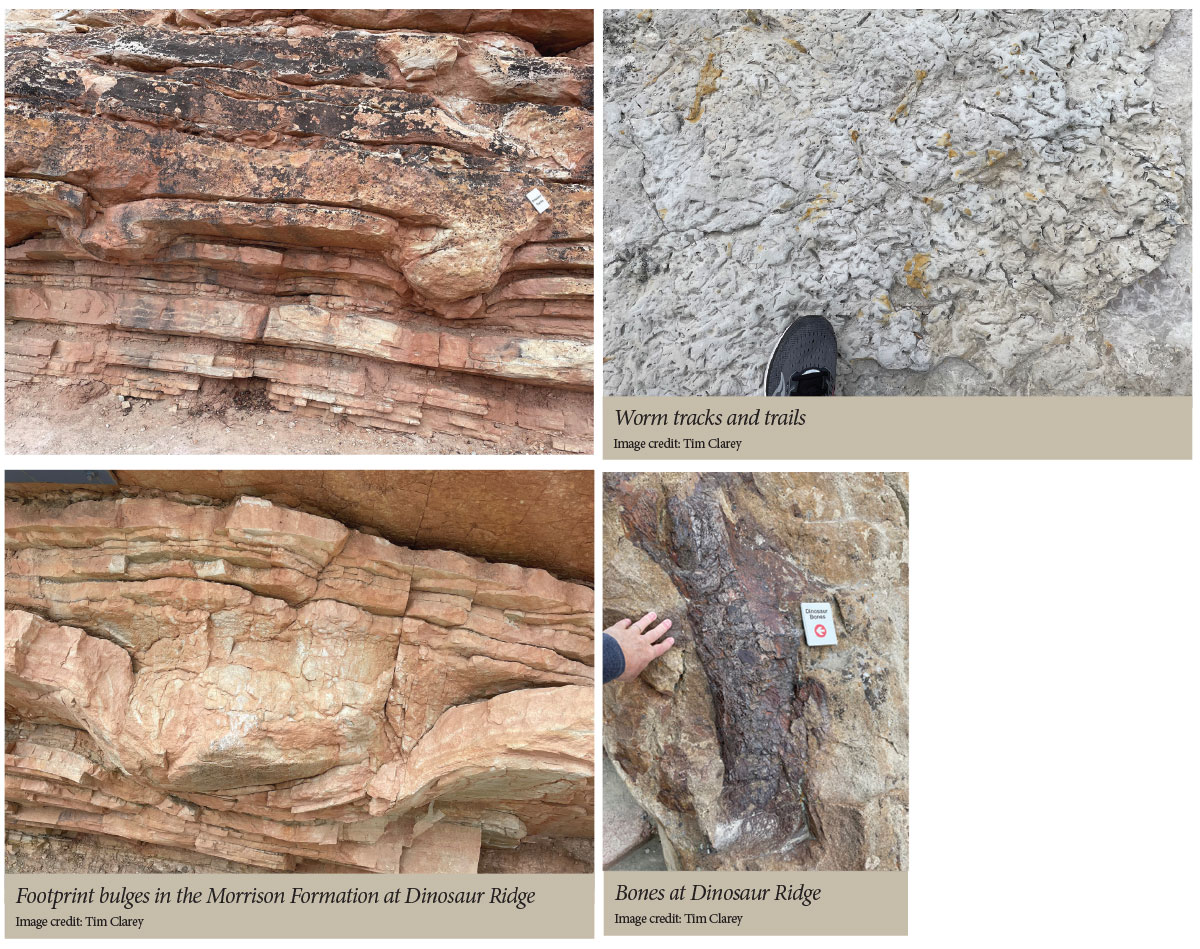

The Morrison also contains downward bulges from dinosaurs stepping into freshly deposited sedimentary layers. These demonstrate that the sediment was still soft when the dinosaurs stepped upon it, compressing several individual beds at once. The bulges are most likely from large, long-necked dinosaurs like Apatosaurus, whose bones were found just a short distance away in the quarries.

Conventional geologists believe that there is a gap of 30–40 million years in between the deposition of the Morrison and the overlying Dakota Group. But the contact between the two shows little evidence of erosion and missing time, being nearly flat along Dinosaur Ridge and beyond. Just one million years of erosion should have marred the contact with gullies, channels, and canyons cut into the Morrison. Flat, planar erosion does not occur today. The Morrison and Dakota units were most likely deposited one atop the other in a matter of days or hours. Thus, the pancake-like deposition is again best explained by the global Flood. Massive tsunami waves washing back and forth across the continent could both deposit and erode vast planar surfaces.

3. The extent of the sedimentary units

The 200- to 300-foot-thick Dakota Sandstone extends from near the Arctic Circle in Canada to northeast New Mexico and Oklahoma and from Minnesota and Iowa to west of the Continental Divide.6 How many shorelines today extend across such a vast, wide region of the continent? Zero. Even a large seaway migrating across North America for eons, as envisioned by conventional geologists, would not result in such a relatively uniform blanket of sand.

The 200- to 300-foot-thick Dakota Sandstone extends from near the Arctic Circle in Canada to northeast New Mexico and Oklahoma and from Minnesota and Iowa to west of the Continental Divide.6 How many shorelines today extend across such a vast, wide region of the continent? Zero. Even a large seaway migrating across North America for eons, as envisioned by conventional geologists, would not result in such a relatively uniform blanket of sand.

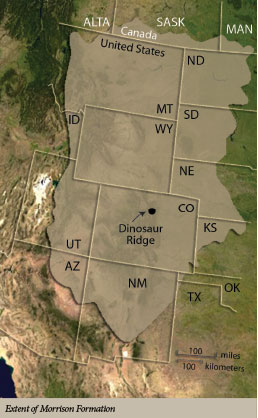

Similarly, the 300-foot-thick Morrison Formation extends from Canada down to southern New Mexico and from central Utah to Nebraska and Kansas. Layers deposited by rivers should be dominated by narrow sandy channels mixed within mostly muddy floodplains. Instead, we see individually deposited, continuous layers in the same order and in the same relative thicknesses across this entire, multistate region. Both the Dakota and the Morrison are best explained by massive water waves that pushed across the continent, leaving mostly continuous beds.

4. Rapid, catastrophic burial

The fossils found at the various quarries by the nineteenth-century dinosaur hunters on the south and west side of Dinosaur Ridge testify to the catastrophic conditions needed to bury these animals. And there are also dinosaur bone beds in the Morrison at hundreds of sites throughout Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah, including Dinosaur National Monument. Bone beds like these do not form in such numbers or across such a vast region anywhere today. They need the special conditions provided by the global Flood.

The fossils found at the various quarries by the nineteenth-century dinosaur hunters on the south and west side of Dinosaur Ridge testify to the catastrophic conditions needed to bury these animals. And there are also dinosaur bone beds in the Morrison at hundreds of sites throughout Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah, including Dinosaur National Monument. Bone beds like these do not form in such numbers or across such a vast region anywhere today. They need the special conditions provided by the global Flood.

The reason so many dinosaurs and other animals left their footprints here is because they likely lived near here in the pre-Flood world. ICR researchers have suggested a long peninsula of lowlands existed where dinosaurs lived, which is now found near the center of the continent.3 Before the dinosaurs were completely swept away by floodwaters, many likely tried to find any remaining land, or at least the shallowest water, where they could still stand and walk. This temporary respite created the Dinosaur Freeway as many dinosaurs congregated there to survive. Eventually, though, they were all swept away.

Conclusion

The remarkable sets of trackways exposed at Dinosaur Ridge could only have been preserved by rapid burial. Beaches and rivers do not preserve vast bone beds, ripples, or footprints. And the massive extent of the sand and mud layers that encapsulate the fossils are better explained by colossal waves washing across the continent than the conventional story of rivers and/or beaches slowly spreading across the continent. The global Flood, detailed in the book of Genesis, provides the perfect conditions to explain Dinosaur Ridge.

References

- About Dinosaur Ridge. Dinosaur Ridge. Posted on dinoridge.org.

- Dinosaur Ridge Trail. Dinosaur Ridge. Posted on dinoridge.org.

- Clarey, T. 2020. Carved in Stone: Geological Evidence of the Worldwide Flood. Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research.

- Lockley, M. and L. Marquardt. 1995. A Field Guide to Dinosaur Ridge, 2nd ed. Morrison, CO: Friends of Dinosaur Ridge and the University of Colorado at Denver Dinosaur Trackers Research Group.

- Lockley, M. and A. Hunt. 1994. Fossil Footprints of the Dinosaur Ridge Area. Morrison, CO: Friends of Dinosaur Ridge and the University of Colorado at Denver Dinosaur Trackers Research Group.

- Macfarlane, P. A. et al. 1998. User’s Guide to the Dakota Aquifer in Kansas. Technical Series 2. Lawrence, KS: Kansas Geological Survey.

* Dr. Clarey is the director of research at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University.