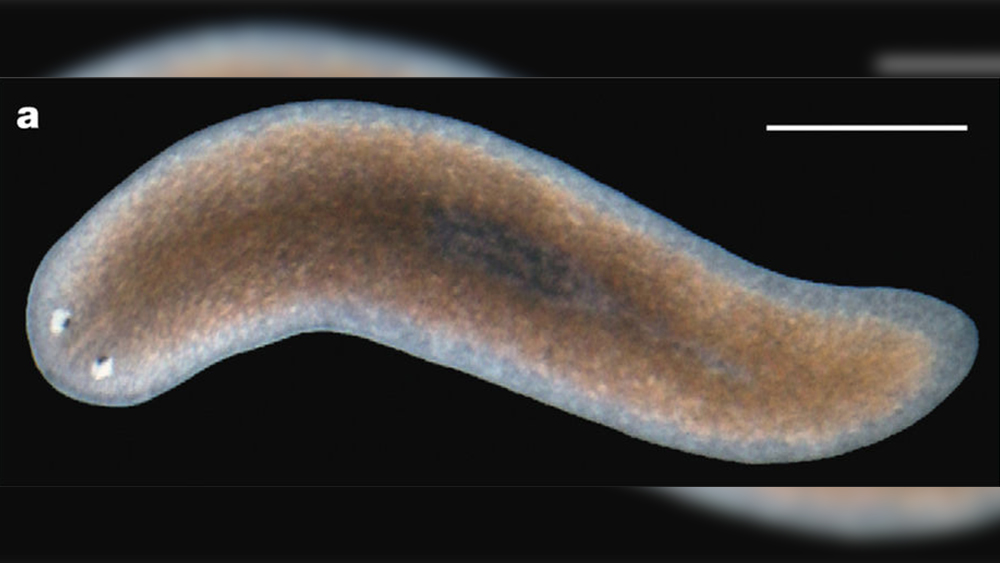

The planaria, a type of flatworm, has an amazing capacity to regenerate a new body from just fragments of tissue. Its genome has just been sequenced. The surprising result is a completely unexpected evolutionary conundrum.

Planarians (S. mediterranea) are a type of freshwater flatworm commonly found between about 3 to 15 mm in length.1 Their size can actually self-adjust within a 50-fold range depending on the amount of available resources.

The evidence for an evolutionary continuum in the DNA of living creatures across the spectrum of life simply isn’t there. ![]()

A variety of creatures can regenerate new tails or limbs, but the planaria can regenerate entire new bodies. You can cut one in half in any direction and you will eventually get two new worms. Some researchers have cut them into hundreds of pieces and observed regeneration from each fragment. The worms’ dynamic bodily engineering allows astonishing regenerative capabilities resulting in the regeneration of complete and perfectly proportioned worms even from tiny remnants of tissue.

To get at the root of the planaria regeneration mystery, scientists just completed the most comprehensive version of its genome using a combination of cutting-edge DNA sequencing and genome mapping technologies.2 Previous attempts had been made, but the genome of the little worm has been difficult to tackle. This is due to large and unusual repeated segments of DNA as well as high levels of genetic variability that has been difficult to eliminate. Also, the planaria genome has a lot higher content of A and T nucleotide letters than G and C, compared to other animals. All of these factors made the DNA difficult to sequence and decipher.

The uniqueness that made the planaria genome difficult to sequence, combined with the new data obtained, resulted in serious contradictions with the evolutionary worldview of the scientists doing the research. One of the main premises of evolution is that you should see a continuum of increasing complexity. New genes and features should be added as creatures become more advanced in the imaginary tree of life. In defiance of macroevolutionary predictions based on supposed related common ancestors, the worms were missing 452 genes commonly found in many other animals. Many of these missing genes are present in alleged prior and later ancestors and associated with common metabolic processes. How could all these genes disappear and then reappear again along the tree of life?

In addition to the supposed loss of important genes that would line up with the evolutionary story, many new types of genes and DNA sequences were discovered in the planaria. It has become a common theme to find conflicts between genome sequences and evolutionary predictions. The evidence for an evolutionary continuum in the DNA of living creatures across the spectrum of life simply isn’t there.

The clearly observable conclusion and best explanation for the conflicts between DNA sequences and evolutionary predictions is Design. ![]()

However, many creatures share similar genes and other DNA sequences for common developmental and metabolic processes. This is a predicted feature of intelligently engineered systems. The clearly observable conclusion and best explanation for the conflicts between DNA sequences and evolutionary predictions is Design. As the Bible states, each uniquely designed creature was created after its kind.

References

- Rink, J. C. 2013. Stem cell systems and regeneration in planaria. Development Genes and Evolution. 223 (1-2): 67-84.

- Grohme, M. A. et al. 2018. The genome of Schmidtea mediterranea and the evolution of core celluar mechanisms. Nature. 554: 56-61.

Stage image credit: Copyright © 2018. Nature. Used in accordance with federal copyright (fair use doctrine) law. Usage by ICR does not imply endorsement of copyright holder.

*Dr. Jeffrey Tomkins is Director of Life Sciences at ICR and earned his Ph.D. in genetics from Clemson University.