Engineered Genomic Changes in Adaptation

by Jeffrey P. Tomkins, Ph.D. | Feb. 27, 2026

Programmed genome rearrangements (PGRs) are deliberate, genetically controlled changes in an organism’s DNA sequence and chromosome structure that occur during normal development or in response to detecting changes in environmental conditions. These PGRs range from single bases to genes to even large genomic regions. They are precisely orchestrated modifications that involve deletions, inversions, duplications, translocations, sequence reductions, or sequence amplifications.

Programmed genome rearrangements (PGRs) are deliberate, genetically controlled changes in an organism’s DNA sequence and chromosome structure that occur during normal development or in response to detecting changes in environmental conditions. These PGRs range from single bases to genes to even large genomic regions. They are precisely orchestrated modifications that involve deletions, inversions, duplications, translocations, sequence reductions, or sequence amplifications.

These are part of an engineered biological program, not random-chance occurrences, and defy the untenable evolutionary concept of random genetic mistakes that are worked on by a mystical selective agent. The following examples clearly demonstrate that PGRs are key elements of a highly engineered regulatory process that purposefully enhances adaptive flexibility. Creatures are engineered with the innate ability to closely track environmental changes and adapt accordingly in targeted ways, as is expected by ICR’s CET model of adaptation.

Immune System Diversification

One of the most important aspects of adaptation is an organism’s built-in system to regulate pathogens that can cause disease and even death. In vertebrates, V(D)J recombination and class-switch recombination are divinely engineered immune-based systems that create diverse antibodies and T-cell receptors.1 V(D)J recombination is the foundational genetic process that gives the adaptive immune system its extraordinary ability to recognize a nearly infinite variety of pathogens. This process occurs in the bone marrow during early B-cell (white blood cell) development. This antigen-independent mechanism literally involves a precise cut-and-paste2 rearrangement of three distinct gene segments: variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J).

The process is initiated by the RAG-1 and RAG-2 enzymes, which recognize specific recombination signal sequences and introduce double-strand breaks in the DNA. Combinatorial variability is accomplished by randomly selecting a single segment from a large pool of available immune genes inherited from the creature’s mother and father. This diversity is further amplified by junctional diversity, where enzymes like Artemis and TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase) randomly add or remove nucleotides at the joining sites. Because these segments encode the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of the antibody’s variable domain, the resulting unique DNA sequence defines the specific antigen-binding site of the B-cell receptor. By leveraging a limited set of inherited genes through these random combinations and junction additions, the human body alone can generate over 1013 unique antibodies—ensuring a defense against virtually any disease-causing pathogen.

If the V(D)J recombination system were not amazing enough, on top of this is added yet another level of engineered complexity and diversity called class switch recombination (CSR). This involves a crucial DNA editing process in B cells that changes an antibody’s functional class (like IgM to IgG, IgA, or IgE) without altering its antigen specificity. This allows for tailored immune responses against different pathogens by swapping the constant DNA region (of an area called the heavy chain) that changes the class of the antibody that performs different functions throughout the time of an infection and afterwards. This irreversible process involves targeted DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in repetitive switch (S) regions. These broken ends are then joined and the intervening DNA deleted. After this, the enzyme activation-induced deaminase (AID) and specific cytokines for proper activation and isotype selection are required to put the whole system into action.

Genome Scrambling and Encryption

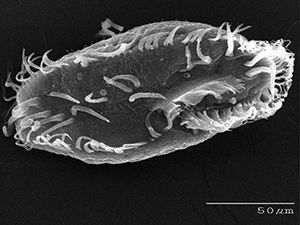

One-cell eukaryotic creatures called ciliates are expanding our knowledge of genome dynamics and taking our concept of PGRs to a whole new level. And contrary to the evolutionary prediction of simple-to-complex in the alleged tree of life, one-cell ciliates are exhibiting astonishing genetic complexity. One particular ciliate genome that has been studied in depth reveals unimaginable levels of programmed rearrangement combined with an ingenious system of encryption.3,4

The ciliate Oxytricha trifallax has two different genomes contained in separate nuclei. One is called the micronucleus. It is dense and compact and used for reproduction. The other is called the macronucleus. It is dramatically rearranged, amplified, and used for the creature’s standard daily living. After two Oxytricha perform sexual conjugation, the old macronucleus is degraded and a new one is formed from the contents of the micronucleus during the development of the new ciliate. This process involves an elaborate cascade of events in which about 90% of the germline DNA (in reproductive cells) is deleted and the remaining fraction is dramatically reorganized and amplified into over 16,000 new chromosomes (called nanochromosomes).4 While scientists previously understood that the genome of this creature underwent a dramatic reorganization, they did not understand the full significance of the phenomena because only the DNA of the macronucleus had been completely sequenced.

Researchers sequenced the micronucleus of Oxytricha trifallax and were surprised at the levels of complexity and rearranging they discovered.3–5 The germline genome of the micronucleus is fragmented into over 225,000 precursor DNA segments that are massively and precisely reordered (unscrambled) during the construction of the new macronucleus and its nanochromosomes (most of which contain only one gene each). However, it gets even more complicated. Many of the genes reconstructed in this process come from numerous individual fragments dispersed across the micronuclear genome—with some even being inverted in their orientation.

So how does a system keep track of and sort out several hundred thousand strings of biological information? As it turns out, an ingenious system of encryption was discovered that enables the decoding of these 225,000-plus fragments. This process uses specialized pointer sequences that flank the macronucleus-designated fragments as a type of encryption and addressing system. In addition, highly specialized RNA guides that are also encoded in the genome mark the specific DNA sections that need to be moved as a type of decryption system. Because even the protein-coding regions of genes (exons) are fragmented, the internal eliminated sequences (IESs) interrupt exons, making their removal a strict requirement for gene expression. Thus, the whole process of slicing and splicing is not error-tolerant but quite precise, involving highly complex systems of encryption and decryption to function properly.

So what is the point of all this mind-bending complexity? Many of the precursor gene fragments can be rearranged in different ways to create more functional combinations or “more bang for the buck,” as they say. Thus, a highly useful feature arising from this radical genome architecture is that a single macronucleus-destined sequence in the micronucleus may contribute to multiple distinct macronucleus chromosomes.

Programmed DNA Elimination

Programmed DNA elimination (PDE) is a highly regulated developmental process discovered in nematodes as a new facet of PGR associated with multicellular development. During PDE, specific genomic sequences are permanently removed from cells destined for normal body cells while the DNA remains intact in reproductive cells.6 This was first discovered in the parasitic nematode Ascaris. Now a recent 2025 research paper confirms that PDE is widespread across the Rhabditidae nematode family, including free-living genera like Oscheius and Mesorhabditis.7 The PDE process typically occurs during early embryogenesis (between the 2- and 16-cell stages) through hundreds of precisely engineered double-stranded DNA breaks followed by the controlled degradation of excluded fragments. This recycles the material involved.

The biological consequences of PDE are highly significant. In Ascaris, approximately 13%–18% of the germline genome is eliminated, including nearly 1,000 genes primarily involved in spermatogenesis and early development that are no longer needed. This serves as a permanent form of gene silencing that effectively prevents the expression of germline-restricted traits in body tissues. Beyond gene removal, PDE targets the removal of repetitive features called satellite DNA. All germline chromosome ends are also removed. They are then remodeled through new telomere additions. This complex genomic editing ensures body cells possess a streamlined genome optimized for their specific functional roles.

Large-Scale Genomic Structural Changes

Stick Insects

In a study published in 2025, researchers examined the genetic basis of habitat adaptation in Timema cristinae, a small wingless stick insect found on two different mountains in California.8 While the insects studied were the same species, the two different body types exhibited different color patterns that were either striped or green. These patterns corresponded to the color schemes of two different host plants that were specific to each mountain (Adenostoma fasciculatum and Ceanothus spinosus). In other words, the genome configurations associated with the PGR of each insect morph conferred highly specific color patterns to provide camouflage against visual predators like birds and lizards.

Using complete chromosome-level genome assemblies, the researchers discovered that these adaptive color patterns are governed by complex structural genomic variation on chromosome 8 rather than more simple features like single gene or small structural differences. They discovered the insect color pattern was associated with large sections of chromosomes that had been moved (translocated) and then also flipped in their orientation (inverted), specific to each of the two mountains.

The scale of these habitat-specific genetic variations was massive: these structural variants spanned approximately 43 million DNA bases containing 299 genes on one mountain habitat and 15 million bases containing 97 genes on the other. The fully functional and habitat-specific complex chromosomal rearrangements originated independently—demonstrating a predictable and repeatable genome alteration mechanism for adaptation.

These large structural variants function similarly to a genomic feature called supergenes. These are genomic blocks where recombination is suppressed, allowing a suite of coadapted genes to be inherited together. The research identified 12 sets of similar but variable genes shared within the structural variants of both mountains that included pro-corazonin and ecdysteroid kinase. These are known to regulate insect coloration and metabolism. In other words, the insects adapt themselves in both color pattern and behavior to avoid predators.

The researchers concluded that while simple inversions are often credited for such polymorphisms, the reality of structural variation can be far more complex. These findings suggest that such diverse genomic architecture may be a widespread, underappreciated innate mechanism for rapid and repeatable adaptation.

Zokors

Zokors are plant-eating, mole-like rodents native to much of China, Kazakhstan, and Siberian Russia known for their powerful digging abilities. They use strong claws to create extensive tunnel systems and to forage for tubers and roots. Zokors have a number of features engineered for subterranean life, including excellent smell, underground hearing, and tolerance for low-oxygen environments.

A recent paper was published investigating how genomic structural variants (SVs), another type of PGR, facilitate zokor adaptation to extreme low oxygen levels at high altitudes (genus Eospalax).9 The researchers generated a high-quality genome assembly for the high-altitude species to identify specific SVs by comparing it to genome assemblies from five other zokor species thriving in low-oxygen levels at lower elevations. The study also included analyzing gene expression and the three-dimensional structure of the genome.

The study identified 18 large inversions (>1 Mb) unique to E. bailey, the species habituating the extreme hypoxic environment. Interestingly, these inversions were often located near chromosome ends. Gene regulation was also altered with specific intronic SVs (noncoding regions) in three key hypoxia-related genes (EGLN1, HIF1A, and HSF1) with upregulated gene expression. This provided a molecular basis for hypoxia tolerance. In regard to the three-dimensional genome, a massive 50-million-base rearrangement on chromosome 1 altered chromatin accessibility. This 3-D structural shift led to the fusion of topologically associating domains (TADs), bringing critical low-oxygen response genes into closer proximity to each other and modifying their expression profiles.10

All of these genetic changes were connected to a number of body adaptations such as larger lung mass, higher red blood cell counts, and increased hemoglobin concentrations (compared to low-elevation zokors), enhancing their oxygen-transport capacity. The research demonstrated that large-scale genomic rearrangements, 3-D genome changes, and smaller SVs are key genetic factors that produce traits that allow zokors to thrive in environments that would be lethal to most mammals.

Human Disease-Based, Targeted Adaptive Changes

Because humans are created in the image of God and, regarding adaptation, are endowed with the mental prowess to simply adjust their behavior and surrounding conditions in response to environmental changes, known major genetic structural variations connected to extreme environments are currently unidentified. However, several recent studies have been published showing that small genetic variants, a small-scale type of PGR, can confer disease resistance.11 In humans, the HBB gene provides instructions for making a protein called beta-globin—a component (subunit) of a larger protein called hemoglobin, which is located inside red blood cells.

In one study, they found that the human HBB gene region contained a segment where a novel single DNA base alteration could produce protection from malaria.12 This is called the protective HbS mutation. Using a novel genome scanning method on large numbers of humans, researchers identified that the HBB region’s variability rate was about 2.6 times higher than the genome-wide average, with distinct rates for specific alterations like HbS connected to malaria resistance. The variability conferred in this region also allows a switch back to a normal state when malaria is not present. Thus, instead of the standard Darwinian model of random mutation and selection, the data instead point to predictable adaptive genetic changes.

Another recent study in humans found that a region in the human APOL1 gene could be altered to provide resistance to sleeping sickness by the Trypanosoma parasite.13 In fact, the data indicated that this single DNA base change is generated more frequently where it’s needed for disease-resistance adaptation. This challenges the long-held idea that mutations arise randomly regardless of benefit. This pattern of adaptive genetic change increased in the relevant disease-challenged population, similar to the HbS mutation with the same implication: genetic change is adaptively directed and not random.

Summary

PGRs from small, single bases to large-scale translocations, inversions, and deletions are not random but engineered features that are directed, purposeful, and repeatable. Furthermore, these innate mechanisms are directly connected to how creatures adapt themselves to challenging environments that would otherwise be impossible to survive in without PGRs. The wide diversity of examples emerging from conventional genomics research point directly to an all-powerful and all-knowing Creator-engineer—the Lord Jesus Christ.

References

- Chi, X., Y. Li, and X. Qiu. 2020. V(D)J Recombination, Somatic Hypermutation and Class Switch Recombination of Immunoglobulins: Mechanism and Regulation. Immunology. 160 (3): 233–247.

- Tomkins, J. P. 2023. Transposable Elements: Genomic Parasites or Engineered Design? Acts & Facts. 52 (5): 14–17.

- Rzeszutek, I., X. Maurer-Alcalá, and M. Nowacki. 2020. Programmed Genome Rearrangements in Ciliates. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 77 (22): 4615–4629.

- Chen, X. et al. 2014. The Architecture of a Scrambled Genome Reveals Massive Levels of Genomic Rearrangement during Development. Cell. 158 (5): 1187–1198.

- Swart, E. S. et al. 2014. The Oxytricha trifallax Macronuclear Genome: A Complex Eukaryotic Genome with 16,000 Tiny Chromosomes. PLoS Biology. 11 (1): e1001473.

- Rey, C. et al. 2023. Programmed DNA Elimination in Mesorhabditis Nematodes. Current Biology. 33 (17): 3711–3721.

- Stevens, L. et al. Programmed DNA Elimination Was Present in the Last Common Ancestor of Caenorhabditis Nematodes. bioRxiv. Preprint posted on biorxiv.org October 24, 2025.

- Gompert, Z. et al. 2025. Adaptation Repeatedly Uses Complex Structural Genomic Variation. Science. 388 (6744): eadp3745.

- An, X. et al. 2024. Genomic Structural Variation Is Associated with Hypoxia Adaptation in High-Altitude Zokors. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 8 (2): 339–351.

- Tomkins, J. P. 2025. The 3-D Genome: A Marvel of Adaptive Engineering. Acts & Facts. 54 (2): 14–17.

- Guliuzza, R. J. 2026. Sickle Cell Research Confirms TOBD Prediction Directed Genetic Adaptations. Acts & Facts. 55 (1): 6–7.

- Melamed, D. et al. 2022. De Novo Mutation Rates at the Single-Mutation Resolution in a Human HBB Gene-Region Associated with Adaptation and Genetic Disease. Genome Research. 32 (3): 488–498.

- Melamed, D. et al. 2025. De Novo Rates of a Trypanosoma-Resistant Mutation in Two Human Populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 122 (35): e2424538122.

Dr. Tomkins is a research scientist at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in genetics from Clemson University

Novel Orphan Genes Aid in Regulated Adaptation

Orphan genes (OGs) are genes that are unique to a specific kind of creature. This is especially significant when creatures that are considered evolutionary ancestors lack these genes. In other words, OGs have no discernable evolutionary ancestry but appear suddenly without any evolutionary precursors—debunking the story of gene evolution and biological evolution in general. And even more interesting is that many OGs play significant roles in environmental ...More...

Orphan genes (OGs) are genes that are unique to a specific kind of creature. This is especially significant when creatures that are considered evolutionary ancestors lack these genes. In other words, OGs have no discernable evolutionary ancestry but appear suddenly without any evolutionary precursors—debunking the story of gene evolution and biological evolution in general. And even more interesting is that many OGs play significant roles in environmental ...More...

Pseudogenes Are Not Pseudo Anymore

Introduction

One of the past arguments for evidence of biological evolution in the genome has been the concept of pseudogenes. These DNA sequences were once thought to be the defunct remnants of genes, representing nothing but mutated genomic “fossils” in the genomes of plants, animals, and humans. However, much research has been published over the past several decades showing that pseudogenes are not only functional but key to organism survival.1,2

More...Long Non-Coding RNAs: The Unsung Heroes of the Genome

Evolutionary theory holds that all living things came about through random, natural processes. So conventional scientists believe the genome has developed through these means, and large sections of it have therefore been assumed to be nonfunctional. These alleged nonfunctional regions supposedly are a source of new gene evolution. But these evolutionary presuppositions of nonfunctionality are being challenged by an unexpected group—members of ...More...

Evolutionary theory holds that all living things came about through random, natural processes. So conventional scientists believe the genome has developed through these means, and large sections of it have therefore been assumed to be nonfunctional. These alleged nonfunctional regions supposedly are a source of new gene evolution. But these evolutionary presuppositions of nonfunctionality are being challenged by an unexpected group—members of ...More...

Genomic Tandem Repeats: Where Repetition Is Purposely Adaptive

Tandem repeats (TRs) are short sequences of DNA repeated over and over again like the DNA letter sequence TACTACTAC, which is a repetition of TAC three times (Figure 1). In the early days of genomics, these tandem repeats were originally designated as nonfunctional or junk DNA. With the exception of a few cases of tandem repeats being involved in human disease, this type of repeat variation was often believed to be neutral in its effect on the ...More...

Tandem repeats (TRs) are short sequences of DNA repeated over and over again like the DNA letter sequence TACTACTAC, which is a repetition of TAC three times (Figure 1). In the early days of genomics, these tandem repeats were originally designated as nonfunctional or junk DNA. With the exception of a few cases of tandem repeats being involved in human disease, this type of repeat variation was often believed to be neutral in its effect on the ...More...

More Articles

- The 3-D Genome: A Marvel of Adaptive Engineering

- Gene Complexity Showcases Engineered Versatility

- RNA Hoops: When Circular Reasoning Makes Sense

- Engineered Parallel Gene Codes Defy Evolution

- Genetic Recombination: A Regulated and Designed Chromosomal System

- Galápagos Finches: A Case Study in Evolution or Adaptive Engineering?

- RNA Editing: Adaptive Genome Modification on the Fly

- Small Heritable RNAs Pack a Big Adaptive Punch

- Trait Variation: Engineered Alleles, Yes! Random Mutations, No!

- Transposable Elements: Genomic Parasites or Engineered Design?

- Epigenetic Mechanisms: Adaptive Master Regulators of the Genome

- Jupiter's Young Moons

- The Final World: Renovation or New Creation?

- Creation Ex Nihilo Through Jesus Christ