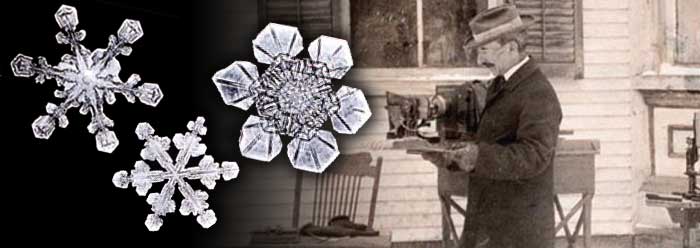

Wilson (Willie) Bentley (1865-1931) was born on a farm in Jericho, Vermont. Jericho was an ideal place to study snow because it was in the heart of the snowbelt, producing an average annual snowfall of over 120 inches.1 Willie was homeschooled until age 14, then he attended public school for several more years.2 By age 14 he wanted to explore the world of science firsthand:

Wilson (Willie) Bentley (1865-1931) was born on a farm in Jericho, Vermont. Jericho was an ideal place to study snow because it was in the heart of the snowbelt, producing an average annual snowfall of over 120 inches.1 Willie was homeschooled until age 14, then he attended public school for several more years.2 By age 14 he wanted to explore the world of science firsthand:

He went from exploring the vastness of the universe, seen in the heavens through a telescope, to the tiny, nearby world seen under the lens of a microscope. The very first money earned in his early teens was invested in a telescope. At night he would look at the stars and the planets, and by day he observed the sunspots on the face of the sun. But one year later an old microscope was to change his life forever.3

A true experimentalist, he meticulously collected large amounts of data on the weather, and completed a variety of pioneering experiments to understand raindrops, frost, solar wind, and moisture. While he was still a boy, his mother, a school teacher, gave him a microscope that he used to observe everything from flowers to snow—and snow especially fascinated him.4

One of his inspirations to study snow was the Bible verses in Job 38 about the “treasures of the snow.”5 When asked why he took an interest in snow, he answered that

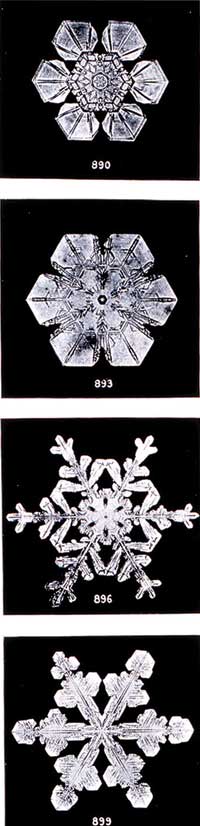

snowflakes were miracles of beauty; and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design; and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind. I became possessed with a great desire to show people something of this wonderful loveliness, an ambition to become, in some measure, its preserver.6

In his study of snowflakes, he learned that almost all snow crystals have six similar branches, and a few very rare ones have three. He at first expected that all snowflakes would be the same, but was surprised to learn that all of those he examined were different. Bentley concluded that, to the best of his knowledge, no snowflake “was an exact duplicate of any other snowflake!,” adding “with profound humility, we acknowledge that the Great Designer is incomparable and unapproachable in the infinite prodigality and beauty of His works.”7

At age 15 he began drawing snowflakes while looking at them through his microscope—no easy task, because most of them melted before he could complete a drawing. At age 16 he learned about a camera that could be used with a microscope. His parents saved the money—and when Willie was 17 they bought him the camera.8 It took him over a year of failures before he finally achieved his goal—a photograph of a snowflake, the first one ever taken. To obtain his pictures, he had to create a complex system that required working rapidly to achieve a photograph before the snowflakes melted.9 Each year he was able to produce at least a few photos—but in some years he managed to make hundreds!

He also carefully studied snowflakes, learning that cold, wind, and moisture variations could produce very differently shaped snowflakes. For example, very cold weather produced three-sided snowflakes.10 He learned that temperatures close to zero degrees were ideal for his work; if the temperature was too warm, the snowflakes melted too fast, and if too cold, they were too brittle and easily shattered like glass.11

He also carefully studied snowflakes, learning that cold, wind, and moisture variations could produce very differently shaped snowflakes. For example, very cold weather produced three-sided snowflakes.10 He learned that temperatures close to zero degrees were ideal for his work; if the temperature was too warm, the snowflakes melted too fast, and if too cold, they were too brittle and easily shattered like glass.11

One interviewer wrote concerning her trip to Bentley’s home in Jericho that her visit gave her a

reason for feeling humble. Out in that remote farmhouse, I sat until far into the night listening to an extraordinary story, the story of how the Great Designer found an interpreter in an insignificant country boy.12

Blanchard wrote that Bentley “saw God in the workings of the universe and in particular in the splendor and grandeur of the snow crystals…he was familiar with the Bible, for in two or three of his articles on snow crystals he quoted some scripture.”13 His work has inspired many a sermon, and one example is below:

In 1925 Bentley said, “Under the microscope….every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated....” The biblical sermon becomes a microscope by which the intricacies of God’s design in the world can be seen by others….God uses his creation to declare his glory to us.14

Bentley believed it is not only “the sheer scope of creation that fills us with praise for the Creator” when examining snowflakes, but the

wonders of God’s handiwork are to be found in the tiniest details of all He has made. One powerful example of this beauty is the intricate design of a snow crystal. Anyone who’s seen snowflakes under a microscope cannot help but be amazed by how beautifully complex they are….Bentley spent nearly fifty years of his life devoted to the study and photography of these fragile jewels. Fascinated both scientifically and artistically by snow crystals, he marveled at what he called the wondrous beauty of the minute in nature. As he observes from the 5,000 photographs of snow crystals he collected, “Under the microscope I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty.”15

Bentley learned that the reason no two snowflakes are exactly alike is because all ice crystals—whether shaped like simple plates, bullets, needles, solid or hollow columns, dendrites, or sheaths—are hexagonal. As they descend from the clouds, they ride air currents up and down for an hour or more through regions of differing temperatures and humidity that leave their marks on snowflakes’ growth and shape. Given how they form, it is extremely unlikely that two complex snow crystals will end up exactly alike. Blanchard wrote that Bentley was puzzled by the fact that the crystal design variations were endless. He said that the explanation “can only be referred to the will and pleasure of the Great First Cause, whose works, even the most minute and evanescent, and in regions the most removed from human observation, are altogether admirable.”16

Nor are all water molecules perfectly alike—about 1 in 1,000 is atypical because it contains a rare form of hydrogen called deuterium. Since even a small snow crystal has about a thousand million billion water molecules, about a million billion will be “rogues.” Given a trillion trillion crystals per year falling on earth, the chance of two ever having the exact same water molecule design is essentially zero. The only exception would be tiny crystals with only ten molecules or so, which might be identical to some other crystal.

Nor are all water molecules perfectly alike—about 1 in 1,000 is atypical because it contains a rare form of hydrogen called deuterium. Since even a small snow crystal has about a thousand million billion water molecules, about a million billion will be “rogues.” Given a trillion trillion crystals per year falling on earth, the chance of two ever having the exact same water molecule design is essentially zero. The only exception would be tiny crystals with only ten molecules or so, which might be identical to some other crystal.

Bentley became the world’s leading authority on snowflakes, and was even selected to write the article in the Encyclopedia Britannica on snow.17 University of Wisconsin professor W. B. Snow bought Bentley’s photographs for years. After Professor Snow had received the 1916-17 picture set from Bentley, he wrote to him as follows:

They are beautiful and give me the most exquisite pleasure, as they will do over and over again, for I shall see them repeatedly during the coming year. You are doing a great work in enabling students and scientists, and people in many walks of life, to see and to appreciate the infinity and prodigality as well as the beauty of nature.18

Bentley also sold his photographs to universities and published them in leading science magazines, including Nature and The National Geographic Magazine.19 At age 66 Bentley published a large, coffee table-size book of his photographs titled Snow Crystals with McGraw-Hill, which in 1962 was reprinted by Dover and is still available today.20 Less than two weeks after his book was published, he walked six miles home in a snowstorm, caught pneumonia, and died two weeks later.

Conclusions

As a “man of science and man of God,” Willie Bentley made important contributions to several fields of science, including meteorology, physics, and chemistry.21 One writer concluded after interviewing Bentley that he specialized in photographing water in some form, including

curious forms of hailstones, raindrops, clouds, still pools, and running streams….But it is the snow that commands his really passionate interest. When he said that he wouldn’t change places with Ford or Rockefeller, there was a ring of exultation in his voice. The indifference and ridicule of some people doesn’t hurt—very much. He feels that he is serving the Great Designer; capturing the evanescent loveliness which, but for him, would be unappreciated—even unseen. And with that role he is content.22

And Levi Smith, president of the local Jericho city bank, said “Mr. Bentley…was very much interested in what the good God had done in the way of snowflakes.”23

Bentley’s work is still honored today24 and has inspired new, vastly improved techniques of photographing the beauty of snowflakes, one of the wonders of God’s creation.25

References

- Martin, J. B. 1998. Snowflake Bentley. New York: Scholastic Inc.

- Blanchard, D. C. 1998. The Snowflake Man: A Biography of Wilson A. Bentley. Blacksburg, VA: McDonald and Woodward, 16.

- Ibid, 19.

- Stoddard, G. M. 1985. Snowflake Bentley: Man of Science, Man of God. Shelburne, VT: New England Press, 3.

- Ibid, 13.

- Blanchard, Snowflake Man, 22.

- Mullet, M. B. February 1925. The Snowflake Man. The American Magazine. 99: 29.

- Stoddard, Snowflake Bentley, 22.

- Bentley, W. A. 1922. Photographing Snowflakes. Popular Mechanics Magazine. 37: 309-312.

- Stoddard, Snowflake Bentley, 33.

- Ibid, 29.

- Mullet, The Snowflake Man, 29.

- Blanchard, Snowflake Man, 18.

- Eswine, Z. 2008. Preaching to a Post-Everything World: Crafting Biblical Sermons That Connect with our Culture. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 163-164.

- Redman, M. 2004. FaceDown. Ventura, CA: Regal Books, 76.

- Blanchard, Snowflake Man, 59.

- Bentley, W. A. 1945. Snow. Encyclopedia Britannica, Vol. 20. Chicago: The University of Chicago, 854-855.

- Mullet, The Snowflake Man, 30.

- Bentley, W. A. January 1923. The Magic Beauty of Snow and Dew. National Geographic Magazine, 103, 112.

- Bentley, W. A. 1931. Snow Crystals. New York: McGraw-Hill; Bentley, W. A. 1962. Snow Crystals. New York: Dover.

- Stoddard, Snowflake Bentley.

- Mullet, The Snowflake Man, 31.

- Blanchard, Snowflake Man, 184.

- Begley, S. and J. Carey. Snow’s Flaky Little Secrets. Newsweek, December 26, 1983, 64; Kemp, M. 2006. The Snowflake Man: Wilson Bentley’s Photographs of Snow Crystals Strike a Chord with Us All. Nature. 444 (7122): 1008; Holden, C. 2010. The Art of Snowflakes. Science. 327 (5966): 627.

- Libbrecht, K. 2008. Snowflakes: Featuring the Amazing Micro-Photography of Kenneth Libbrecht. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press.

* Dr. Bergman is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Toledo Medical School in Ohio.

Cite this article: Bergman, J. 2011. Snowflake Bentley: Man of Science, Man of God. Acts & Facts. 40 (12): 12-14.