We’ve all noticed the many layers of rock strata as we drive along a road cut. It seems as though we are driving through a huge “layer cake,” cut open to expose the inside. Grand Canyon looks this way. Most of the exposed layered rocks are sedimentary rocks. It appears one layer was deposited directly upon another. The “stack” of layers might have been tilted, folded, or faulted subsequent to deposition, but the layers were flat-lying when first deposited. Thus, the ground surface usually represents the top of the final layer in any particular region.

For decades the discipline of geology was dominated by this “layer cake” thinking, and even today it is a convenient theory for geologists. But scientists have discovered that geologic layers are not always laid down one after another. Sometimes, a sequence of layers is laid down simultaneously from left to right, not from top to bottom.

All geologists recognize that major geologic events accomplished much of the deposition of the rocks we see. Tsunamis, underwater mudflows, gravity slides, turbidity currents, etc., are all capable of laying down sediment rapidly. Only energetic flow can carry along and eventually deposit large particles. As such a flow slows, finer grains drop out. These events mirror our understanding of the dynamic Flood of Noah’s day.

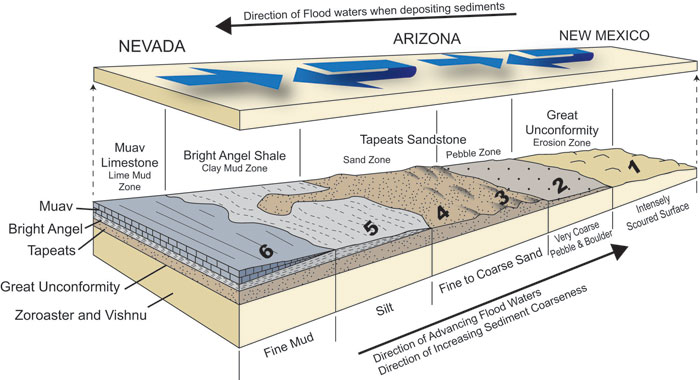

Consider a continual supply of sediment being propelled underwater. The large sand grains drop out at the leading edge of the flow as the velocity slows and water curls back, but the finest grains remain mobile. More sediment-laden water follows, with the larger grains resting just beyond the prior deposit, and the finer grains come to rest on top of the coarser grains. This continues and ultimately results in two or more blanket-like layers, all of which were simultaneously deposited laterally, rather than in a consecutive and vertical manner. This concept is clarified in the accompanying diagram,1 which specifically explains the coarse-to-fine-grained Sauk Megasequence in Grand Canyon. The sequence consists of the coarse-grained Tapeats Sandstone, the fine-grained Bright Angel Shale, and the even finer-grained Muav Limestone, each of which has enormous horizontal extent and a comparatively minor thickness.2 The concept applies, in general, to all such megasequences and in many locations. Many of the Flood rocks were deposited this way.

References

- Adapted from Figure 4.12 in Austin, S. 1994. Grand Canyon: Monument to Catastrophe. Santee, CA: Institute for Creation Research, 69.

- Morris, J. 2012. Gaps in the Geologic Column. Acts & Facts. 41 (2): 16.

* Dr. Morris is President of the Institute for Creation Research.

Cite this article: Morris, J. 2012. Lateral Layers of Geologic Strata. Acts & Facts. 41 (3): 15.